CFDA: WHY FAUX IS THE FUTURE

I recently penned an article for the prestigious Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) about the amazing, sustainable and ethical developments in material innovation.

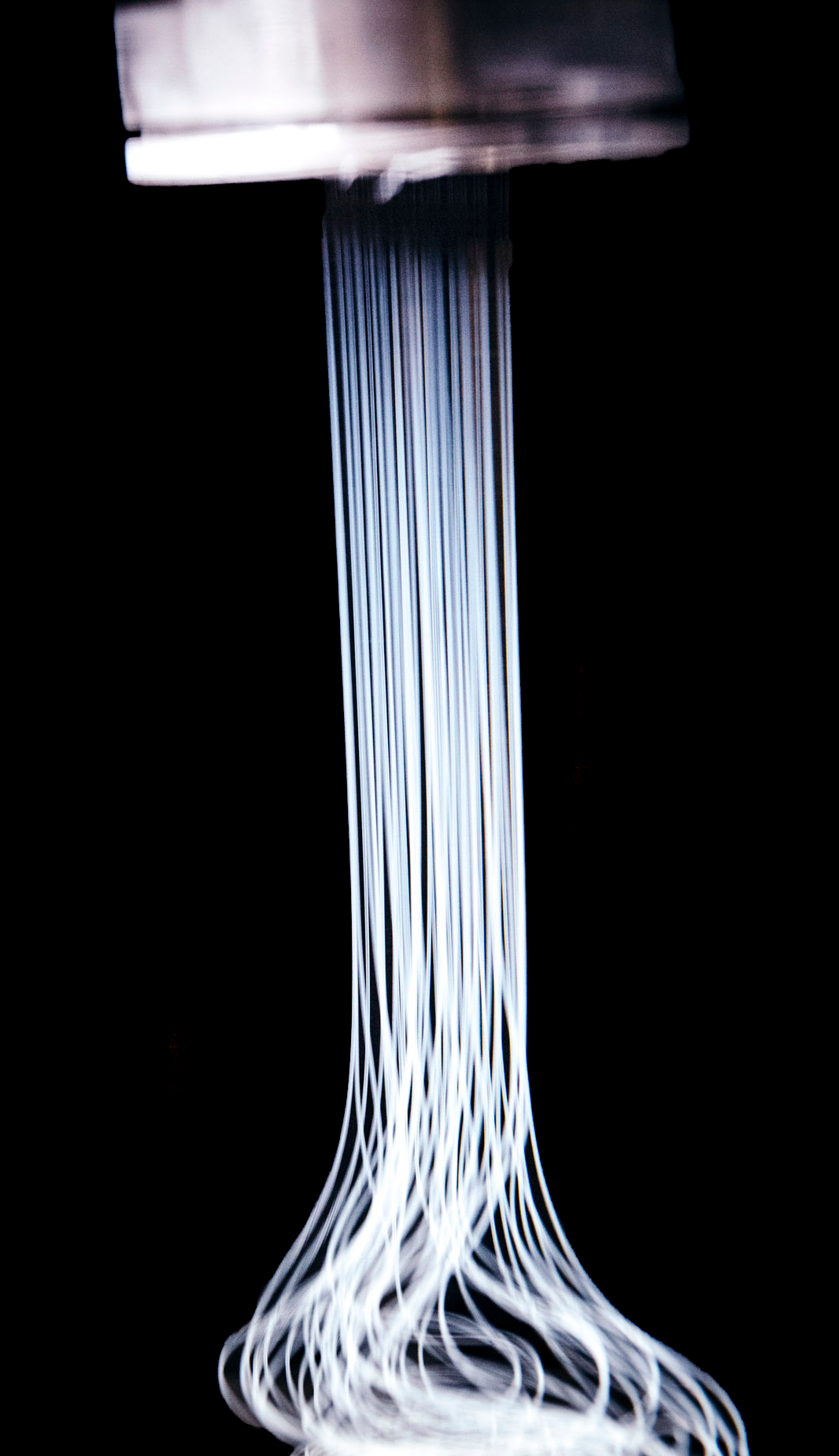

EcoPel’s recycled PET fur and coconut oil-based fur

Somewhere in London, the company FUROID™ is growing actual fur pelts and wool in a laboratory without any animals involved in the process. In Paris, Ecopel™ is crafting future-furs from recycled ocean plastic or coconut oil, and they’re on the verge of launching a top-secret sustainable faux with a major label that they couldn’t yet share with me. In the United States, Bolt Threads™ is synthesizing their protein-based mycrosilk without any spiders or worms involved and coaxing mycelium into their mushroom-leather product Mylo™ which appeared in the MET Museum’s Is Fashion Modern show as a gorgeous bag that Stella McCartney designed. In New Jersey, Modern Meadow is perfecting their product Zoa™ – which is leather grown from cells. Across the globe companies like Provenance, Geltor, Amsilk, Spiber, and Vitro Labs are all working on biological protein fiber technology using emerging systems like cellular agriculture and biofabrication.

And it doesn’t stop there. Primaloft is developing hi-tech, biodegradable and recyclable insulation that outperforms feather down. Econyl is tackling the single worst cause of ocean plastic pollution (abandoned fishing nets) and turning them into high-performance and infinitely recyclable nylon thread. Frumat, Vegea, Apple Eco Leather, Orange Fiber, Fruitleather Rotterdam and others are using fruit waste to make leather-like and soft cashmere-like materials. Lebenskleidung is redefining shearling and faux-fur with organic cotton. Ecovative and MycoWorks are using fungus to create skins, and companies like Bloom and Algiknit are harnessing algae to make polymers and fibers – it seems the innovations are endless.

ZOA™ by Modern meadow, Ecopel, and Bolt threads Mycrosilk™

All together the innovations are an awe-inspiring window into the future that will someday soon replace the cruelties all too common in animal supply chains from anal electrocution on fur factory farms to the way snakes are killed for their skins (they inflate them to death with an air compressor or water hose). This wave of innovation makes me optimistic. Make no mistake, this is the real-time unveiling of the next industrial revolution and it centers design customization through biology, ethics and sustainability.

No matter what the fur industry may say about faux fur, the best faux furs still outperform animal furs in regard to environmental impacts and health hazards. Scientific data supports this, as outlined in the CE Delft Study, the Pulse of the Fashion Industry Report from Copenhagen Fashion Summit / Boston Consulting Group and Kering’s own Environmental Profit & Loss tool. Numerous studies show that faux has a smaller impact that animal fur: (HSUS, 2009; Poulsen et al, 2003; van Dijk M. 2002; Smith, 1991), which requires fossil fuels, formaldehyde, chromium, azo dyes and results in toxic eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems near fur farms, which is highlighted in the documentary “The Farm in My Backyard”. Even the World Bank listed fur-dressing as one of the five worst global toxic-metal polluters. This of course does not mean that plastics aren’t a problem (they are), but it requires we at least acknowledge the bigger problem and put a stop to insidious, well-funded lies. Ads that are currently running here in the US have already been shut down by French and Dutch advertising standards authorities for false and misleading “natural”, “sustainable” and “ethical” claims.

Not too long ago, real advertisements for domesticated dog and cat fur coats and gloves, made in New York, circulated in mainstream periodicals. They’re featured in my recent book, Fashion Animals. Also featured are ads selling tiger, monkey and polar bear furs, including a dramatic 1917 illustrated Vogue cover depicting a fur-clad woman spearing a bloody polar bear to death. Just imagine if a mainstream magazine ran these today!

In the last century our understanding of animals and nature has changed drastically. Where once we saw an inexhaustible stockpile of resources, we now know that nature has limits and that animals are so much more than fiber-factories. When fur farming started at the turn of the twentieth century – it was a plan to reap profits amid a landscape of dwindling wildlife in which fur-bearing animals (as well as birds and so-called “pests”) were being hunted to extinction – a blow that the toolache wallaby, sea mink, Arabian ostrich, Falkland Islands wolf, Tasmanian tiger, quagga, passenger pigeon, carolina parakeet, and huia did not escape — and so many other species never recovered from. We can learn a lot from the past missteps of our society’s appetite for animal skins, even when the market says otherwise.

We didn’t wait for the market to protect cats, dogs and endangered species used in fashion or even immigrant child garment workers in NYC plumeries or southern cotton mills. Sadly, there will always be a market for exploiting the most vulnerable, and each one of those protections came with heavy opposition. And that’s the context in which we need to view NYC Council Speaker Corey Johnson’s current Intro 1476 to ban the sales of new fur in New York City.

Over the last couple of months, the fur industry has been caught on tape telling supporters to lie about where they live to city council members, they’ve been caught actually paying people to testify against a fur ban in California, and their tactics of hiring expensive lobbying firms to weaponize race has been exposed by The Intercept and The New York Times. They want us to believe that compassion is extreme, but an industry requiring the confinement or trapping and killing of 100,000,000 animals per year is somehow not extreme.

A view of animals as mere products is becoming more and more fringe because it flies in the face of science. Researchers are documenting non-human animals’ advanced emotional and social complexities, and what’s clear is how much we’ve underestimated their capacity to suffer and to value their own lives. So what does that mean for the fur industry? Sadly, they represent an outdated worldview that is far more medieval than modern. In the age of transparency and rapidly evolving understanding of non-human animals, a fashion object can not be beautiful if it’s made in a horribly ugly way. It isn’t possible to confine wild animals to small wire cages for their entire lives, depriving them of every natural instinct; to run, play, dig, hunt, explore and kill them using horrendous yet “industry-standard” methods like anal-electrocution or gassing and still have a coat or collar that we call “beautiful”.

As consumer awareness grows, designers will inevitably make superior and ever-increasingly customizable design decisions, that are less harmful to animals and the environment. This is the momentum of an advancing society; beauty that is matched by efficiency, functionality and an inspiring set of ethics. There is so much opportunity in this emerging space, and New York City has this moment to revitalize it’s garment industry that has been disappearing since the mid-1900s through innovation. New York City has the talent, resources and expertise to become the global leader.