Fur, Get It?

On GQ.com's "The Trends That Matter" Fall 2012 trend report, author Jim Moore lists fur as one of this season's major must-haves. But is there more to this trend than meets the guy? Let's take a closer look.

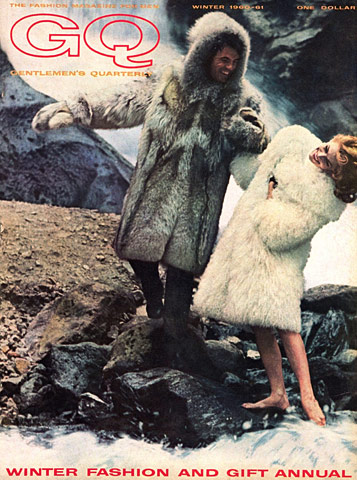

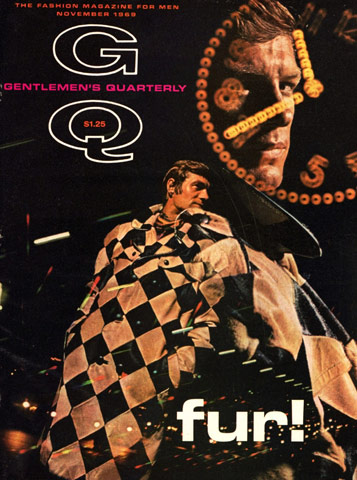

It's practically shoved down our throats that fur equals luxury, and not simply because it's warm and soft. As the report admits, "with so many technical materials used in the body, it's nice to have a luxury touch". Like what most arctic explorers and astronauts choose who brave temperatures beyond anything New York or Chicago could muster, hi-tech synthetics are the way to go if staying warm is the true ambition in wearing fur. Fur, however, far removed from functionality is one of the most sought-after symbols of power - financial, sexual, and direct power over nature. But has this symbol truly lasted the test of time since GQ itself asked the question "Should animals become coats?" on the cover of their November 1970 magazine? We're skeptical.

It's practically shoved down our throats that fur equals luxury, and not simply because it's warm and soft. As the report admits, "with so many technical materials used in the body, it's nice to have a luxury touch". Like what most arctic explorers and astronauts choose who brave temperatures beyond anything New York or Chicago could muster, hi-tech synthetics are the way to go if staying warm is the true ambition in wearing fur. Fur, however, far removed from functionality is one of the most sought-after symbols of power - financial, sexual, and direct power over nature. But has this symbol truly lasted the test of time since GQ itself asked the question "Should animals become coats?" on the cover of their November 1970 magazine? We're skeptical.

Only last year, Olivier Lalanne, editor-in-chief at Vogue Hommes International and deputy editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris did not mince words about the tactile (and olfactory) lack of luxury associated with fur when, in his own words, he published:

“Fur is as much a no-no as ever. It's sexually dodgy, feels funny, and reeks when it's rained on.”

And why the need for a fur trimmed hood to define luxury? Isn't that a bit démodé? Isn't the limited definition of luxury in itself against the forward momentum of fashion - or is this feeling of fashion evolution, season after season only an increasingly accelerating and regurgitating optical illusion of progress toward something better? So what's our beef with fur? Read on.

FUR IS BAD DESIGN

While the definition of good design continues to be contentiously debated, we can be confident in saying that good design exists somewhere in a balance between expertly executed aesthetics, ease of functionality, and efficient use of resources. The trend of fur, however, is almost entirely based in pure frivolity. For the average consumer, it's a decoration that is barely functional outside of semiotics, and easily replaceable by cutting-edge, future textiles. The singular future-fur featured in the GQ report was from J.Crew (right) but the rest of the garments in the report showcased the old-fashioned stuff. As for aesthetics, there is very little control over fur short of selective breeding and dyeing. It's stiff, bulky, and designed by nature to decompose. The amount of nasty substances required to keep a pelt from festering off of one of those hoods is disturbing enough for Fur Famrers in Nova Scotia to violate the provincial Environmental Act, enough to have ads banned claiming that fur is "eco-friendly", and enough for the fur industry to launch a "Fur Is Green" campaign that has seriously backfired after scientific research proving otherwise was published, putting a major damper on the efficiency claims. It's an industry that the World Bank once ranked as the world’s fifth biggest toxic metal polluter, an industry responsible for killing threatened and endangered species despite claims otherwise, and an industry being banned or limited in more countries every year. What good design that is not edible needs to be refrigerated at forty-five degrees so it doesn't rot or get attacked by insects during the spring and summer? What good design is so inefficient that it requires the raising, feeding, watering and housing of 11 animals for about every 2 pounds of product? What industry with the premiere claim to luxury is capitalizing in countries like China with little to no environmental or animal welfare regulations, yet produces and consumes more fur, including domestic cat and dog, than anywhere else in the world?

FUR IS A SYMBOL, BUT NOT A GOOD ONE

Fur is a visual symbol invoked to represent wealth, sex, power, class and even a connection to nature and animals, the latter being a good desire in and of itself, albeit perversely executed via fur. The marketing and PR forces behind the fur industry, as the New York Times shed light upon recently, rely on these definitions to make money and must keep the production process concealed. Instead we are shown a procession of famous, powerful people, and those "rebelling" against wholesome do-goodery flaunting their furs. But as production transparency transforms the semiotics of fashion, it is no longer possible for a fur coat to be symbolic of power, for it is only a performance of power against the already powerless. It can not be symbolic of anything but "I deny animals can suffer, and therefore deny modern science", "I hate animals", "I can afford this" or "I have no idea how this was made". As fashion philosopher Lars Svendsen says,"In order for violence to be pleasurable, it must appear to be justified (or fictional)." And both justifications and fictionalizations of the fur production process have many millions of dollars behind them.

The lure of easy power over the defenseless, and a masculine fantasy of themselves as rugged frontiersman is what many men who wear fur or who are trappers are after, though few realize or admit it.

FUR IS GROSS

The ethical implications of animals bred, trapped or hunted, siphoned into fashion objects, obscured and silenced in the fashion industrial complex, is a shameful evasion of our fatal attraction to animals. But the real gross stuff, the nastiness of which you'd never see, smell, feel or hear an honest depiction in the "journalism" of fashion is the actual raising or tapping and killing of the animals for their pelts. As investigation after investigation after investigation has revealed, it is not a gentle process. Companies famous for their fur-trimmed hoods like Canada Goose like to make claims about ethical sourcing of fur, but organizations like Fur Bearer Defenders have had to do the work of deconstructing and rebutting their many claims. It is a process involving a violent struggle to live against the inevitable fate of death by anal or genital electrocution, gassing, neck-snapping, bludgeoning, starving, bleeding, dehydrating or any number of other methods. But the death is not necessarily the worst part, it is the languishing prior to death that bothers me the most. On farms, the deprivation of any natural physical or social behavior like digging in dirt or swimming (mink are semi-aquatic) these wild animals evolved to fulfill is evident in their neuroses. Have you seen an animal struggle in a trap? Editor Tim Woody of Alaska Magazine recently published an article about a trapped wolf he stumbled across, “This is no way to see a beautiful animal.” Feeling “pity, and anger” he documented the inglorious demise of one of the planet’s most maligned animals. Look closely at the image (right) and you can see the wolf's eye, acknowledging Tim. Look deeper into that eye and you might find it difficult to deny that the wolf has his own perspective, outside of what any trapper would like to believe for convenience sake.

“The wolf’s struggle was evident for yards around the wooden post to which the trap was anchored. Trampled snow was covered with splintered wood, chunks of ice, and blood spatters. But this once-powerful animal was done fighting. Its eyes watched us, but it was too tired to hold its head up and track our movements. Its breathing was shallow. We wondered how long it had been there facing its slow, painful death. There is no state law mandating how frequently trappers must check their traplines. We wished we had a pistol, because the scene in front of us was one of dreadful suffering. A merciful bullet would have made everyone feel better.”